By Dr. Ashley Holding

Background

The rise of plant-based leather alternatives appears unstoppable. There is growing interest in cruelty-free, plant-based and low carbon alternatives to conventional leather, especially as veganism and climate conscious buying become top priorities.

Established media is picking up on it, too. Only a few days ago, The New York Times hosted an interactive article titled “Fabrics From Your Fridge”. In it, they praised the virtues of different materials such as mushroom-based alternative leathers like Mylo and Mycoworks, “apple-based” leathers such as Frumat and “grape-based” leather such as Vegea and others.

In particular, the partnership between Stella McCartney and Bolt Threads with its Mylo leather alternative (a technology itself licensed from Ecovative Design, another US start-up) received a large amount of international media coverage. Despite the impression given by the media campaign, you need to read the small print to find out that this novel material is neither fully bio-based, nor biodegradable, nor plastic-free. Mylo itself tells us that it is finished with a bio-based polymer, most likely a partially-bio based polyurethane. Mylo was certified to be 50-85% bio-based, which would fit with the hypothesis of a natural material (mycelium) finished with a partially bio-based polyurethane (i.e, a plastic which is formed from both petroleum and bio-based feedstocks, but with similar properties to conventional petroleum-based polyurethanes). Otherwise, it is not clear what makes up the rest of the non bio-based composition.

A few months ago, Paula Lorenz and I posted an article titled ‘Marketing Hype or Reality: Why Plant and Plastic Hybrids are the Worst of Both Worlds’ here on The Circular Laboratory. Some brands and consumers are interested in purely biological processes: the idea of a material that can break down seamlessly into nature, returning its carbon to the natural carbon cycle. On the other hand, others want to focus on materials, typically various kinds of traditional petroleum-based or even bio-based plastics, which can be recycled again and again.

While it is possible to have a material that is recyclable as well as biodegradable and even compostable (able to be degraded under realistic composting conditions), the majority of “plant-based” leathers fall into a category which is neither – they are mixtures of plastics (typically polyurethanes) and natural materials. One particular example we highlighted was the example of Desserto, a material which we uncovered (based on its listing on a material database that has since promptly been deleted) was mostly polyurethane, with only a small amount of natural material mixed in.

This is far from the only type of material like this, and similar criticisms apply to the various ‘fruit’ leathers and mycelium-based leathers, which are often mixed with non-degradable binders and coatings to somewhat approximate the performance of leather. The main advantage in pursuing this approach is the potential for a slightly lowered carbon footprint due to displacement of some of the weight of plastic present in conventional PU-based ‘vegan’ leathers.

Some publications picked up our criticism of some of these materials, such as this recent piece in Sourcing Journal, which spoke to a number of other experts and stakeholder in this field. Our original article was cross-posted to a number of other blogs and even translated into other languages.

It’s clear we struck upon somewhat of a nerve: in general, people don’t like being misled, and they were somewhat shocked to discover that most plant-based leathers were not, in fact, fully plant-based, even though it wasn’t any particular kind of secret – it just seemed that way due to highly selective marketing claims being made.

What Happened Next In This Story?

I always thought, at the time, it would be fairly simple enough to do some laboratory tests which could establish the true composition of some of these materials, if anybody was of the mind to do so. In fact, this is exactly what has happened. In the journal Coatings, a peer-reviewed scientific article was published which compares a range of leather alternatives with natural leather. The article was authored by FILK Freiberg Institute, an independent institute specialised in the testing of leather and polymer composite materials.

They confirmed our previous assertion that a major class of plant-based leathers were mostly made of polyurethane, typically attached to a polyester or cotton backing textile. They also compared a couple of fully bio-based alternatives such as Muskin and Kombucha, but the main finding was that their properties were very far from that of actual leather.

How did they manage to confirm this?

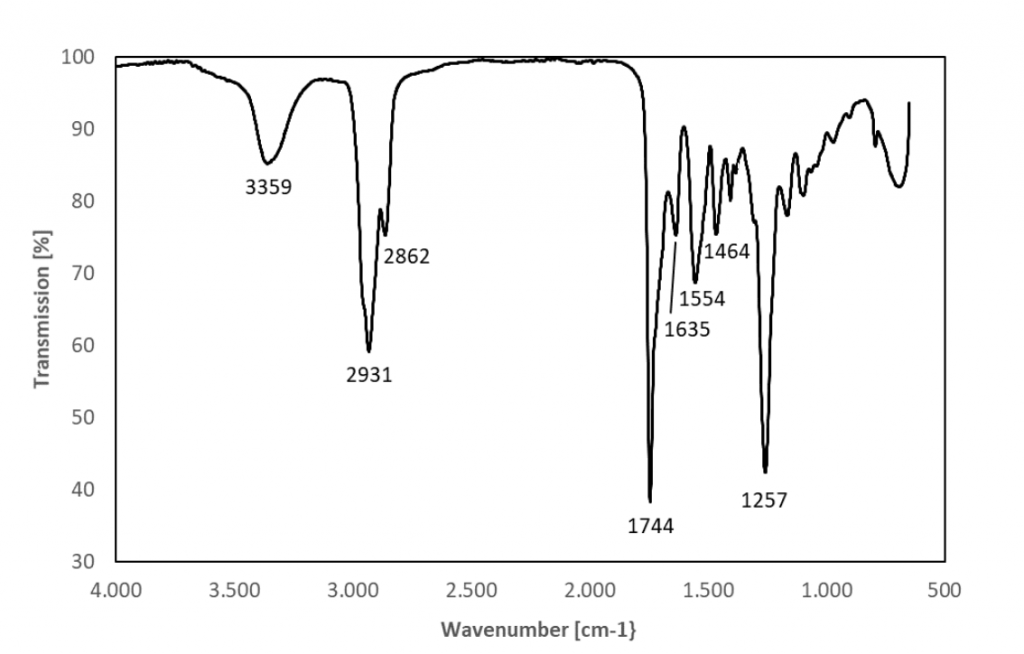

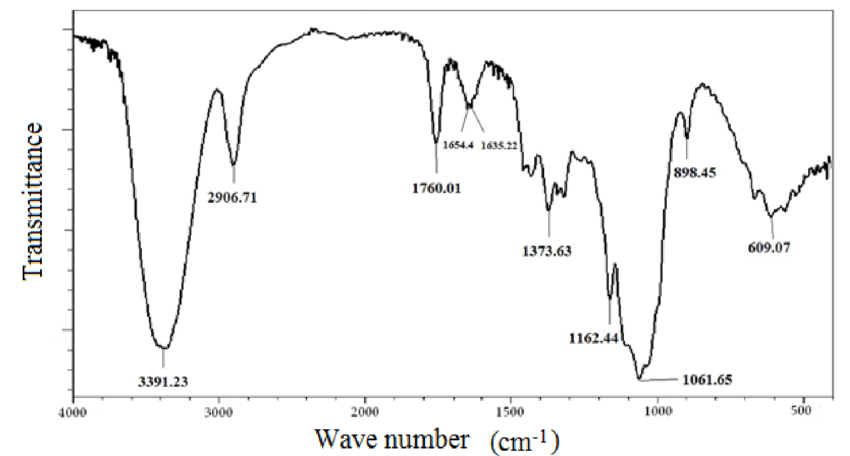

In chemistry, an infra-red spectrum is a sort of “molecular fingerprint” of a chemical, polymer or material, which can show us the types of molecular bonds and thus the chemical structures which may be present in a material. It’s not easily quantitative, but it is used to give a rough qualitative determination of the components or a mixture, especially when compared to reference spectra of other materials.

The one example that they show is of the material we have previously discussed: Desserto Cactus Leather. The infra-red spectrum below confirms that the material is mostly polyurethane, and not (mostly) a plant-based natural material biopolymer, such as cellulose or other polysaccharides (shown for comparison below). However, the specific proportions of the material are difficult to quantify from infra-red analysis alone, and this is something that the authors highlight.

Reprinted from https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6412/11/2/226

Reprinted from http://pubs.sciepub.com/wjee/3/4/1/index.html

In the paper, we also see magnified cross sections of the materials that were studied. Here, we can see the foamed polymer and natural material layer (b) with the polymeric coating (a) and the textile backing of Desserto leather (c):

Reprinted from https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6412/11/2/226

More shockingly, the study found that some of the leather alternatives contained traces of explicitly banned chemicals, in particular Desserto, Appleskin, Vegea, and Piñatex, the group of plastic-coated textile leathers. One of the poorest scoring materials was actually the Desserto cactus leather, which contained five restricted substances including butanone oxime, toluene, free isocyanate, an organic pesticide called folpet, and traces of a phthalate plasticiser. In some of the other alternative leather samples, toluene and plasticisers, and the solvent DMF were detected. However, the article does not clarify the absolute levels in which these contaminants were detected.

The team also tested the physical properties of the materials and compared them to natural leather. Unsurprisingly, none of the materials really matched the purpose of leather. Some came closer than others, and particularly the non-coated or hybrid materials Muskin and Kombucha fell quite short in terms of strength. Of course, depending on the application, some brands may tolerate differing physical properties as they may wish to incorporate the unique properties of some of the materials into their product design. In essence, it is pretty tough to replicate the natural fibrous collagen network found in animal skins, so it is quite clear that the materials are substitutes or rough approximations of real leather.

So What’s Next?

There is clearly a need for continued innovation and improvement in this field. Conventional leathers can currently be sourced chrome-free and tanned using vegetable-based processes, reducing the impact in some key areas. And there are other innovators working on this issue, who are attempting to create fully plant-based and plastic-free alternatives to animal leather.

What we need to be clearer about is the claims that are being made about certain materials and the way in which these stories are told to the public. It will ultimately undermine consumer confidence in the long term, if every new plastic and natural material hybrid is hailed as a ‘breakthrough sustainable innovation’. Innovators, manufacturers and brands need to honestly depict the limitations of certain approaches and the challenges that lie ahead, without glossing over the details or obscuring key pieces of information that would allow consumers to make informed decisions.

[…] submitted by /u/emkay123 [link] […]

[…] submitted by /u/Alaishana [link] […]

[…] Source: ‘Plant-Based’ Plastic Leathers: An Update, According to Science – The Circular Lab… […]

[…] toxic chemicals, phthalates and PVC. Unfortunately, their claim to be non-toxic was disproven by a study done in early 2021 that picked up on five restricted substances in the final product, including butanone […]

[…] compounds, phthalates and PVC. Unfortunately, their declare to be non-toxic was disproven by a study done in early 2021 that picked up on 5 restricted substances within the ultimate product, together with […]

[…] toxic chemicals, phthalates and PVC. Unfortunately, their claim to be non-toxic was disproven by a study done in early 2021 that picked up on five restricted substances in the final product, including butanone […]

[…] more – findings published by The Circular Laboratory identified that plant-based leathers like Desserto have only a minimal proportion of natural […]